Best Practices for Preparing, Conducting, and Using Depositions

Getting the Most out of Depositions in Your Case

by Casey Sullivan

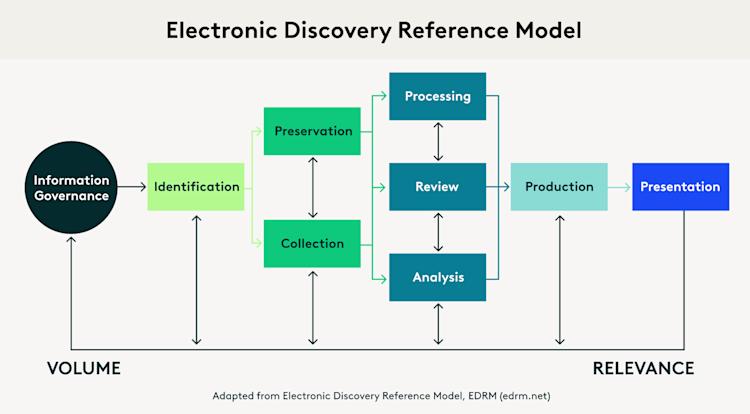

In ediscovery, we spend a lot of our time discussing phases of the Electronic Discovery Reference Model, or EDRM. There are companies and solutions focused on the “left side” of the EDRM (identification, preservation, and collection), other companies and solutions focused on the “right side” of the EDRM (analysis, processing, review, and production), and still other companies and solutions offering end-to-end ediscovery. However, for many of those end-to-end providers, the right “end” stops at production.

Perhaps the phase that gets discussed the least by ediscovery professionals is the one that drives what happens in all others: the presentation phase.

Every other ediscovery phase, from identification through production, should be conducted with presentation in mind. To present evidence as exhibits in a deposition, trial, or other presentation event, that evidence must first be identified, preserved, collected, analyzed, processed, reviewed, and produced.

Depositions are a vital part of the discovery process. They are used to generate evidence for the ultimate presentation event – trial – but they are also presentation events themselves, in that evidence, whether physical evidence or electronically stored information (ESI), is often presented during the process of deposing the witness.

Well-planned and well-executed depositions can literally make your case in court.

Depositions can be used to authenticate existing evidence, generate new evidence, or even identify discovery deficiencies, which may require additional discovery – or sanctions to be issued if spoliation of evidence has occurred.

Because of the deposition’s significance, it’s important to understand how to prepare for it, and that includes identifying your goals for the deposition, the questions you plan to ask, and the documents and exhibits you will present to the witness.

Developing your strategy in advance and building the story you want to tell gives you the best chance of accomplishing your goals for each deposition.

During the deposition, you execute that strategy to ensure you meet your goals of authenticating or generating evidence and identifying discovery deficiencies. The deposition testimony then becomes evidence that you organize for trial, presented in a manner that maximizes the value of that testimony.

Well-planned and well-executed depositions can literally make your case in court. Here are some best practices for preparing for them, conducting them, and organizing the evidence obtained from them for use in trial.

Preparing for Depositions

To prepare for and conduct productive depositions, it’s important to understand the basics. Here, we review what a deposition is, the common types of depositions, the rules governing how they are conducted, and the types of witnesses typically being deposed.

What Is a Deposition Anyway?

The concept of a deposition is relatively straight-forward. A deposition is the pre-trial taking of testimony from a witness, under oath and before a court reporter. By definition, depositions occur outside of the courtroom and before trial.

A deposition is part of permitted pre-trial discovery. It’s set up by an attorney for one of the parties to a lawsuit (defendant or plaintiff) and demands the sworn testimony of the opposing party , a witness to an event, or an expert intended to be called at trial by the opposition.

If the person requested to testify, also known as the deponent, is a party to the lawsuit or someone who works for an involved party, notice of time and place of the deposition can be given to the other side’s attorney. If the witness is an independent third party who’s reluctant to testify, a subpoena must be served.

The testimony is taken down by the court reporter, who will prepare a transcript if it’s requested and paid for, which assists in trial preparation and can be used in trial either to contradict (impeach), refresh the memory of the witness, or be read into the record if the witness is not available.

Types of Depositions

There are two types of depositions that can be used in litigation, oral depositions and written depositions.

Oral Depositions

The most common type of deposition is the oral deposition, which is taken in person and recorded by a court reporter. This type of deposition allows for questioning of the witness by both the attorney taking the deposition and the attorney representing the other party. Today, oral depositions are often recorded on video, but not always.

Oral depositions have traditionally been conducted in person, though conducting depositions by telephone has been a typical alternative when the witness is located in a different state or country from where the case is being tried and it’s not practical to conduct the deposition in person.

However, in recent years, virtual depositions via a web conferencing platform like Zoom have become more popular – especially in 2020, when social distancing necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic forced many to work and meet remotely. According to research conducted by PwC, remote depositions accounted for approximately 90% of all depositions during the height of the pandemic. That same report from PwC suggests that over 50% of depositions will occur remotely after all pandemic-related restrictions are lifted, and that number is expected to continue growing in the coming years.

Video Recordings of Oral Depositions

Oral depositions may also be recorded, with the video recording used in the same manner as a deposition transcript.

Video depositions are becoming increasingly common, as they can capture more nuanced and consequential information, to bring to life the emotional elements of deposition testimony that may be lost in a text-only transcript.

Without video, the transcript serves as the only record of the oral testimony.

Written Depositions

The other type of deposition is the written deposition, which is taken in writing and not recorded. Before a deposition of written questions is sent to the deponent, it must be sent to the other parties in the lawsuit. Any other party may object to a question or request that additional (cross) questions be asked, serving the purpose of cross-examination. A third party, such as a notary public or process server, presents the questions to the deponent. The questions are answered in the presence of the third party, who also attests that the answers are properly sworn.

Rules Governing Depositions

As there are two types of depositions, there are also two rules in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or FRCP, that govern how depositions are conducted.

Rule 30. Depositions by Oral Examination

FRCP Rule 30 covers the most common type of deposition – by oral examination. It addresses:

(a) when a deposition may be taken;

(b) notice of the deposition;

(c) examination and cross-examination, record of the examination, objections, and written questions;

(d) duration, sanction, and motion to terminate or limit;

(e) review by the witness and changes;

(f) certification and delivery, exhibits, copies of the transcript or recording, and filing; and

(g) failure to attend a deposition or serve a subpoena and expenses.

Rule 31. Depositions by Written Questions

FRCP Rule 31 covers depositions by written questions. It addresses:

(a) when a deposition may be taken;

(b) delivery to the officer and the officer’s duties; and

(c) notice of completion or filing.

Rule 45. Subpoena

In both cases, the deponent’s attendance may be compelled by subpoena under FRCP Rule 45. (The United States Courts provides a template for a Rule 45 subpoena here.)

If the deponent wishes to avoid testifying, they can file a motion to quash the subpoena, which would then be heard by the court and either granted or denied.

There is also one rule for depositions in the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, or FRCMP.

Rule 15. Depositions

FRCMP Rule 15 covers all types of depositions for criminal cases. Depositions in criminal cases are less common than in civil cases, but, under this rule, “[a] party may move that a prospective witness be deposed in order to preserve testimony for trial. The court may grant the motion because of exceptional circumstances and in the interest of justice.”

State rules regarding depositions vary regarding specific requirements, so it’s best to consult the rules for your specific state.

Types of Witnesses

There are three types of witnesses typically deposed: fact witnesses, expert witnesses, and character witnesses.

Fact Witnesses

A fact witness is someone who has firsthand knowledge of the facts of the case. A fact witness can testify about what they saw, heard, or experienced. For example, a spectator of an automobile accident can be a fact witness testifying what they saw happened and, potentially, who may have caused the accident.

FRCP 30(b)(6) permits a party to notice or subpoena the deposition of “a public or private corporation, a partnership, an association, a governmental agency, or other entity and must describe with reasonable particularity the matters for examination.” So a 30(b)(6) witness is a fact witness – except that they are testifying regarding the corporate entity’s knowledge, not the individual deponent’s.

Expert Witnesses

An expert witness is someone with specialized knowledge or skills who can offer opinion testimony. An expert witness can provide insights that go beyond the scope of a fact witness.

For example, a digital forensic examiner could provide testimony regarding whether an electronic file submitted for evidence is authentic or if it has been tampered with.

Character Witnesses

A character witness is someone who can attest to the character of a party to the litigation. In a criminal litigation, they typically provide testimony about the defendant.

Checklist for Deposition Preparation

The goals of a deposition depend on the type of deposition being conducted and the type of witness being deposed. Here are several best practices for preparing to conduct depositions and tips for preparing the documents and exhibits you plan to use.

Download a copy of this checklist here.

Preparing to Conduct a Deposition

Have a clear understanding of the purpose of each deposition. This includes understanding the key issues in the case, the objectives for each issue, obtaining background information on the witness, and using that information to understand how each of the issues and objectives relate to the specific witness.

Address scheduling considerations early. This includes notifying opposing counsel with proposed witnesses and dates, identifying how the deposition(s) will be conducted (e.g., in-person or virtual, recorded or just transcribed), choosing a court reporting service, and any special considerations, such as the need for an interpreter.

Research the law and know the rules. It’s important to know the rules, especially when it comes to rules that govern how depositions are conducted and what objections are acceptable.

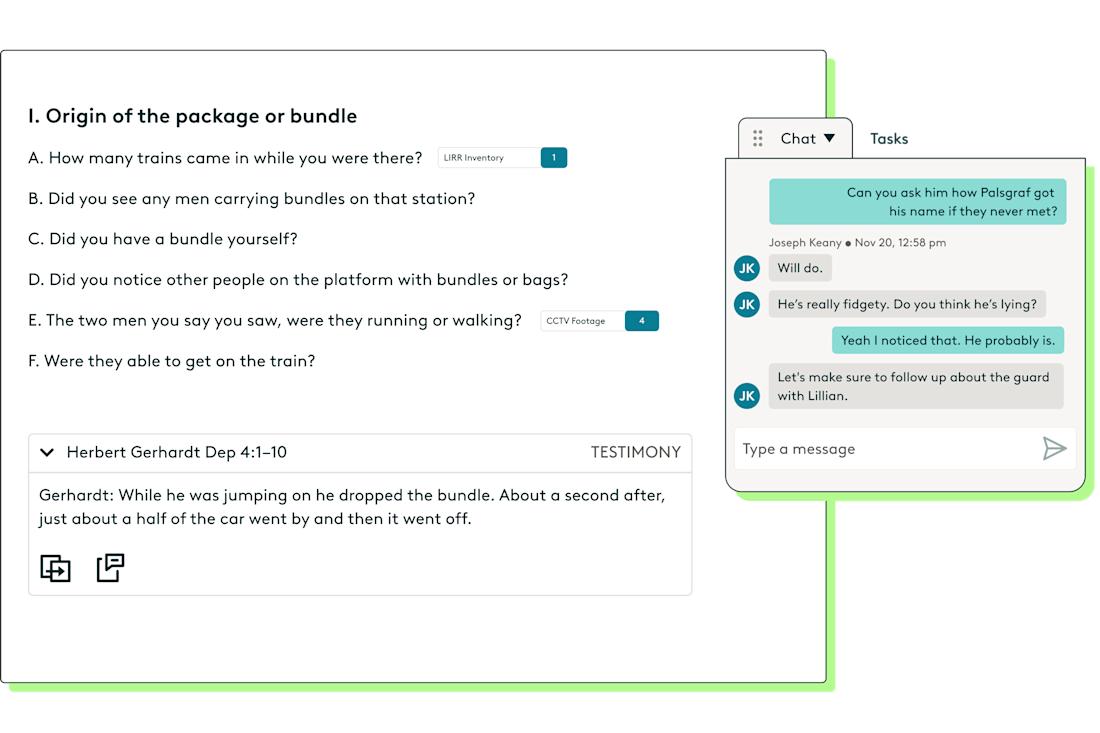

Be organized. This includes building an outline that ties to the issues and objectives identified above and preparing a list of documents that supports each outline item. However, it’s important to be flexible with the outline, as you want to be prepared to respond with follow-up questions based on how the witness responds. The outline should be a guide, not a script.

Bring copies of key documents. Quick access to key documents can greatly improve the effectiveness of an examination, allowing you to control the pace and tenor of the deposition. In addition to key documents, bring copies of the civil rules, which have provisions governing conduct and objections permissible during a deposition; a copy of the subpoena to mark the document as an exhibit to illustrate what the witness is required to bring to the deposition; and an interrogatory disclosure of what the witness will testify about.

Locating and Preparing Documents and Exhibits

A workflow for locating and preparing documents and exhibits can be broken down into three main components: 1) identifying documents to review, 2) culling a review set to identify potential exhibits, and 3) identifying the final set of exhibits.

Identifying Documents to Review

You will want to perform searches within your document collection to identify documents that could be used as exhibits. Examples of search topics include:

Name of the witness. Search for the last name, or if the last name is common, run a proximity search using both the first and last names.

Email addresses. Search for known email addresses of the witness, including any variations of those addresses.

Issues and topics. Search for key issues and topics that you plan to address with the witness, regardless of whether the witness is particularly tied to those documents by name or email address.

The results of each search can be added to a review set to be considered for inclusion as exhibits during the deposition.

Identification is not limited to search, however. Specialized tools can help you make sense of large bodies of documents, without requiring you to know what issues or topics to search for at the onset. For example, consider integrating the following tools into your workflow for a better understanding of the potential evidence in your case early on:

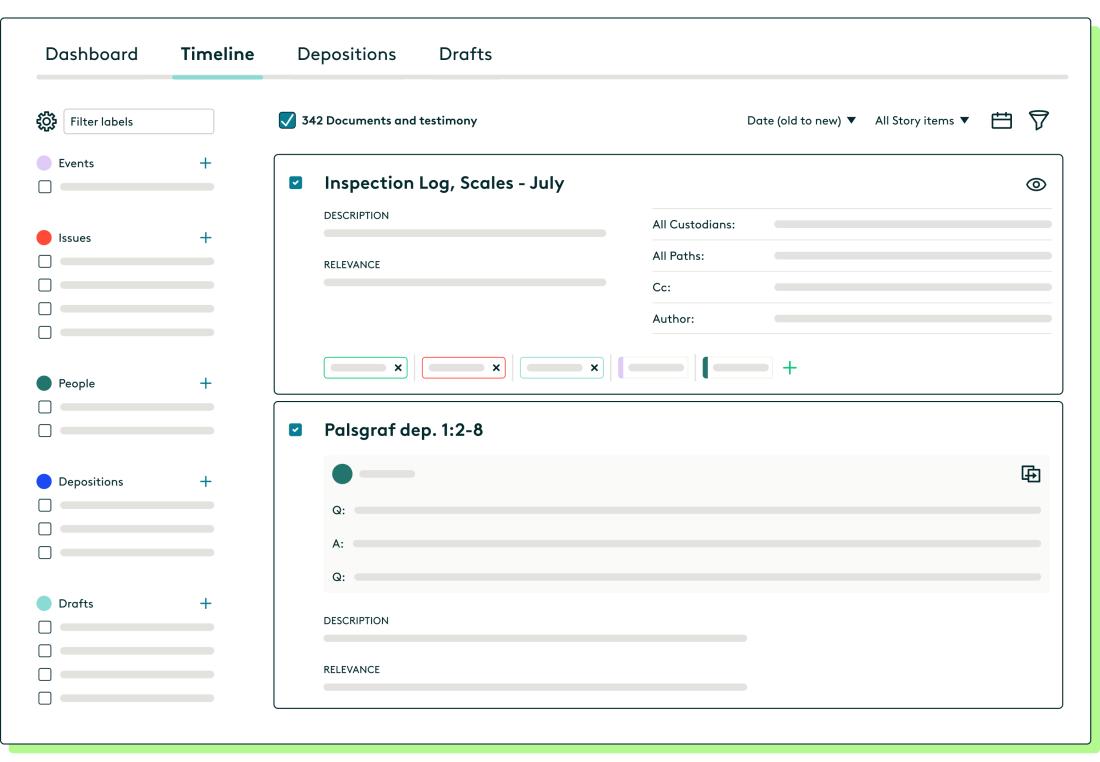

Clustering. Concept clustering technology, such as Everlaw Clustering, applies machine learning to your documents, grouping them by conceptual similarity, so you can see key themes at a glance. Clustering allows you to survey the connections between millions of documents at once, then seamlessly zoom in on a single piece of evidence.

Communication Visualizer. Communication visualizations illustrate the connections between the different actors within a document set. With tools such as Everlaw Communication Visualizer, you can see who was talking to whom and at what frequency, quickly establishing key players or identifying outliers for further investigation.

Data Visualization. Data visualization tools present an overview of the documents in your database by summarizing their characteristics visually, without requiring document-by-document review. For example, with Everlaw’s Data Visualizer, you can visualize all documents or search by a particular term and then visualize various properties within that set, whether filtering by date, party, metadata, or other characteristics.

Predictive Coding. Predictive coding helps you find documents most likely to be important to your review by learning from existing review decisions to predict how your team will evaluate the remaining, unreviewed documents. This allows you to surface the hottest documents based on their prediction score. Learn more about how Everlaw’s predictive coding works here.

Powerful but accessible ediscovery software, such as Everlaw, can be an essential tool not just in identifying key pieces of evidence, but organizing that evidence for presentation during depositions.

Culling the Review Set to Identify Potential Exhibits

Once documents have been retrieved and placed into a review set, they can be reviewed and tagged as potential exhibits, based on the known topics and issues to be discussed during the deposition. Search and review are often iterative, in that review of documents may identify additional issues and topics that could be included in the deposition, leading to further searches and more documents to be reviewed.

Identifying the Final Set of Exhibits

Once the review process is complete, the final set of exhibits is determined and the exhibits can then be numbered for reference during the deposition.

Best Practices for Conducting Depositions

Once you’ve prepared for the deposition, it’s time to conduct it, and you want to conduct it in a manner that best supports your goals for the deposition. Here, we discuss best practices for conducting a deposition, including pacing and strategy, as well as considerations for referencing evidence during a deposition.

Download your deposition best practices checklist here.

10 Best Practices for Conducting a Deposition

There’s a saying that “you never get a second chance to make a first impression.” You also never (or at least rarely) get a second chance to accomplish your goals in a deposition. Here are 10 best practices for conducting a deposition.

Collaborate actively. Document review and deposition preparation can involve many different individuals. Having tools that allow you to effectively collect the insights gathered throughout the process not only helps create the most cohesive understanding of events, it can help you catch what you might have missed. When preparing for a deposition, leverage tools such as collaborative drafting and timeline-building capabilities where multiple individuals can add dates, labels, and annotations to documents and testimony. When conducting a deposition, features like chat can be used to quickly communicate information, such as which exhibits to introduce next.

Act composed and confident. It’s easier to maintain control over the proceedings if you appear self-assured. If you’re nervous and don’t feel composed and confident, fake it until you make it!

Be professional and courteous to all parties involved. This is especially important when examining the witness, as the more at ease they are, the more likely you will get cooperation and candid answers.

Don’t blindly agree to the “usual stipulations.” There's no such thing, at least from a judicial standpoint. You should either decline to do so or clarify on the record what is meant by that term.

Prioritize. Some goals (and the questions designed to accomplish those goals) are more important than others. FRCP Rule 30(d) limits depositions to “1 day of 7 hours,” unless otherwise stipulated or ordered by the court. Devote the majority of your time to the most important goals and questions.

Ask simple, short questions with one subject. Complex questions lead to convoluted and unhelpful answers. Be direct.

Don’t ask any unnecessary questions. Each deposition question should be aimed at accomplishing a desired result.

Actively listen. If you are too focused on following your script of questions or on taking notes, you may miss an opportunity to follow up on important information obtained from a witness’s answer.

Follow up. Make sure that the question was fully answered on the record. Don’t accept answers that are unresponsive, vague, ambiguous, or incomplete. Follow up until the question is sufficiently answered.

Don’t take victory laps. If you win on a particular point, resist the temptation to let the other side know. There is plenty of time to follow up after the deposition with a motion for summary judgment or other motion to address the issue.

Keeping these best practices in mind will help ensure a smooth process and a productive outcome for your deposition.

Referencing Evidence During a Deposition

There are several reasons you may want to use an exhibit with a witness. They include:

To obtain more information about the exhibit. For example, to understand medical bills or receipts for expenses that are part of a damages claim by a plaintiff.

To establish the witness’s lack of knowledge of the exhibit. For example, to rebut claims the witness is making.

To authenticate the exhibit. For example, asking a records custodian to authenticate business records or a photographer to authenticate a picture.

To refresh a witness’s recollection about key events. For example, using an accident report to help a witness recall additional details about an auto accident.

To create an exhibit during the deposition. For example, if asking a witness to draw the intersection where an auto accident took place, that drawing could then become an exhibit for the deposition.

In each case, you want to understand the goals for each exhibit and the expected outcomes for introducing it.

Maximizing the Use of Your Deposition Evidence

Once the deposition has been conducted, the post-deposition workflows of organizing testimony, handling deposition video recordings and written transcripts, organizing deposition evidence, and preparing that evidence for trial will enable you to maximize the use of your deposition evidence. Leveraging technology through tools such as Everlaw Storybuilder can help automate these post-deposition workflows.

Organizing Testimony

In Everlaw, you can upload a transcript to a Deposition object you’ve already created. Once you’ve successfully uploaded your transcript, you can then begin to search for and highlight key testimony to help organize it. You can also search across the entirety of your transcript for key terms, moments, or responses, or search across specific sections of the transcript.

Crucial pieces of testimony can be added directly to your timeline. Information from your deposition can be supplemented with dates, descriptions, relevance, and labels, to help build the most comprehensive view of your case.

Handling Deposition Video Recordings and Written Transcripts

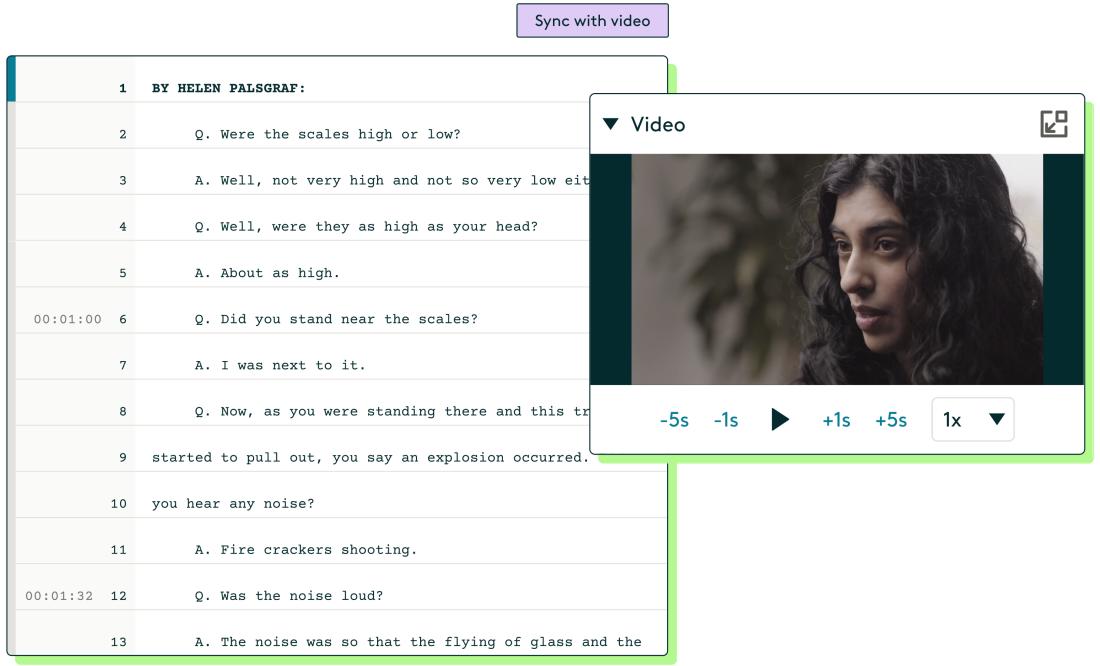

Because meaning often goes beyond the written word, videos of deposition testimony can provide a valuable advantage when building a case, allowing you to unearth subtleties that may otherwise be lost.

In Everlaw, you can upload a video deposition and its accompanying transcript for easy playback and review. Users can then add notes to timestamps and create compelling video clips to present at trial.

As depositions can sometimes stretch over several hours, if not days, being able to find the information you need in video recordings without having to review them in their entirety is key.

Because meaning often goes beyond the written word, videos of deposition testimony can provide a valuable advantage when building a case.

Tools such as Everlaw can sync deposition videos and accompanying transcripts. This enables attorneys to not only read the transcript onscreen while watching the deposition or trial-video footage, but to also search the video record for key words and phrases at any point, quickly finding important testimony and key excerpts. At trial, the litigation team can use the synchronized transcripts to quickly locate and play back passages of important testimony in court to respond in real time to court events.

Preparing Evidence for Trial

With documents marked as exhibits in your depositions, labels added to key testimony, and video depositions synchronized, you can effectively manage the end-to-end process of deposition and trial preparation by integrating key portions of testimony into critical documents.

Crafting a strong narrative is a fundamental part of trial preparation. The client’s case boils down to the story the attorney tells, regardless of exhibits, expert testimony, or any of the other details that make up a case. If the story is feasible, believable, and memorable, it’s much more likely the judge and jury will look at it favorably. In contrast, if an attorney can’t present the case well, neither the judge nor the jury will likely give a lot of credence to the evidence presented. The ability to leverage technology to organize the evidence to create that strong narrative is your best advantage in trial preparation.

Putting Best Practices Into Action

Presentation is the culmination of the ediscovery life cycle. It’s the phase that all other phases are built around.

Crafting a strong narrative is a fundamental part of trial preparation.

Depositions are a key discovery tool for capturing evidence, while also being a presentation event as well.

How well your team prepares for, conducts, and uses the depositions in your case can significantly impact your case outcome.

A combination of following best practices, leveraging technology, and collaborating to organize the evidence obtained can enable you to get the most out of your depositions, and that strengthens your chances for a positive case outcome.

Take this guide with you. Download your copy of Everlaw's guide to deposition best practices here.

Casey Sullivan is an attorney and writer based out of San Francisco, where he leads Everlaw’s content team. His writing on ediscovery and litigation has been read by thousands and cited by federal courts.