Handling Mobile Data in Ediscovery

Nearly all Americans (97%) own a mobile phone of some type today, and most (85%) own a smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center. People spend a good portion of each day using their phones – an average of three hours and 15 minutes – and check their phones an average of 58 times per day.

We are literally addicted to our mobile devices.

Our mobile phones have become extensions of ourselves. We carry them everywhere, and use them for work and during downtime to text and email colleagues and friends, snap photos, shoot videos, and watch movies – among a whole host of other activities.

On average, a person has 40 apps installed on their phone. Millennials typically have more than 67 installed apps. Additionally, mobile devices track so much data about us, including our location, time spent on the device, our biometric data (such as fingerprint or face scans), health and fitness data, and more.

Given the continuous use of mobile devices by so many of us and for so many things, it’s not surprising that the data generated by those devices is increasingly relevant in ediscovery. In civil litigation cases, text message communications are a frequent source of discoverable electronically stored information, or ESI. In criminal cases, global positioning system, or GPS, location data is often used to put the perpetrator near the scene of the crime or to provide an alibi for a potential suspect. Photos and videos are often applicable to both types of litigation cases. Those are just two examples of how mobile device data can be relevant to litigation.

For legal professionals, the discovery of mobile device data comes with a number of challenges. Collecting it can be complex and time-consuming. Potential custodians are often unwilling to provide their devices for collection simply because they can’t stand to part with them for any period of time. Many organizations resort to spot collections of data from devices via screenshots, which may require affidavits or testimony to be authenticated.

Search and review of mobile device data is another challenge. Unlike email, in which each message is a snapshot of the “thread” of the conversation to that point, searching with search terms for relevant text messages will typically only retrieve individual messages, not additional messages contextually linked with the conversation. Even determining what constitutes a “conversation” within text messages is hard to do. Many organizations are forced to arbitrarily define a conversation using a time frame, such as an exchange that took place within a particular day or over the lifetime of communications between the parties.

In the 2023 State of the Industry Report from eDiscovery Today, almost a third (31.9%) of 377 respondents said that mobile device data either always or usually plays a role in their cases, and less than half (49.4%) of respondents said it appears in at least half of their cases. While mobile device data is frequently considered a potential source of discoverable ESI, many organizations decide that the ediscovery burden outweighs the potential value of the data. Assessing the proportionality of discovering mobile device data tends to be a case-by-case analysis.

This chapter discusses considerations for handling mobile data in ediscovery, including the most common forms of mobile data and the challenges associated with the ediscovery process, relevant case law rulings, and best practices for reviewing and producing mobile data in ediscovery.

Common Forms of Mobile Data in Ediscovery

Our mobile devices track an enormous amount of personal information. Only some of that data is discoverable in litigation. It’s important for legal professionals to be familiar with the forms of mobile data that are most commonly relevant in litigation.

Text Messages

Communications between key individuals can contain important evidence in a case. Text messages are the most common type of data included in mobile device discovery.

There are two types of text messages:

SMS, or Short Message Service: The simplest and most common type of text message, supported by many mobile devices. SMS typically allows for a maximum of 160 characters per text message.

MMS, or Multimedia Messaging Service: Messages that provide the ability to include text, pictures, videos, emojis, music, and other content.

The implementation of MMS messages depends on the carrier and operating system. For example, iMessages between iPhone users can track when someone is responding and whether the message was delivered or read, which could be important in discovery.

Photos and Videos

Photos and videos are another common source of mobile data that can be responsive in litigation. In both civil and criminal cases, they can supply key evidence to illustrate what happened, for example, in a “slip and fall” or auto accident – even to provide a recording of someone in the act of committing a crime. Unless the photos or videos have been sent to another device, they only exist on the mobile device and must be collected from the device itself.

Notably, native photos and videos on mobile devices contain key metadata that aids in authentication of the evidence and gives additional evidentiary value. Along with the date and time the photo or video was taken, mobile phones also retain the associated GPS data. The metadata can be important evidence to illustrate, for instance, a person’s location in relation to a car accident or whether an item was damaged when and where it has been claimed.

Notes and Voice Memos

Note files and voice memos are additional data sources that only reside on the mobile device, so they should be considered in discovery and may need to be included in custodian questionnaires to determine whether they should be collected.

Phone Logs

Mobile devices track calls sent and received and the duration of the calls. These phone logs can be important to identify communication patterns and potential custodians or to inspire deposition questions regarding the subject of specific calls. While these phone logs are typically available from the cell carrier via subpoena, they can be collected from the mobile device itself.

GPS Location Data

Mobile devices track a user’s location and can do so even when location services are turned off. With more than 307,000 cell towers in the U.S. alone (not to mention public Wi-Fi networks, which also track location), location tracking can be quite precise. GPS location data is also typically available from the cell carrier via subpoena and is frequently used as evidence in criminal cases to arrest or clear suspects. Law enforcement sometimes even uses geofence search warrants to identify potential suspects. This happened in the aftermath of the January 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riots when Google geofence data initially identified 5,723 devices as being in use at or near the Capitol during the riot.

Biometric Data

Mobile devices can also store biometric data. Fingerprint and face scans are used as a convenient layer of user authentication. Biometric data related to fitness and health (such as heart rate) are often collected in conjunction with wearables such as Fitbits or Apple Watches. While fitness and health data can be requested directly from the makers of wearable devices, it can also be gathered from the mobile device itself and has become more frequently relevant in recent years in select criminal and civil cases.

App Data

Of course, there are literally millions of mobile device apps, and most of them store data unique to the app. As of mid to late 2021, there were 2.89 million apps published in the Google Play Store and 4.37 million apps published in the Apple App Store.

When it comes to app data, the first question to ask is whether it is also available online. Many chat apps store message data online as well as on the mobile device, which means it can be collected there without the need for the device. There can be exceptions. Data may linger on the mobile device even after it expired or was deleted, which can happen with ephemeral messaging apps, so it’s important to consider that possibility.

Regardless, discovery of app data that may reside solely on the mobile device is addressed on a case-by-case basis and is typically only considered when it is proportional to the needs of the case.

Common Challenges Associated with Mobile Data

Legal professionals face several challenges associated with the discovery of mobile device data and should address several questions.

How Do You Collect Mobile Data for Discovery and Litigation?

There are two types of collection methods available for mobile data: non-forensic collection and forensic extraction.

Non-forensic collection involves the use of a utility that enables selected files to be collected from the mobile device, including text messages, photos, and videos. This method is typically appropriate when the goal is simply to obtain evidentiary files without concern for preserving deleted evidence. Examples of non-forensic collection utilities include the following:

iMazing: Saves and views iPhone text messages, photos and videos, phone call history, and other data.

TouchCopy: Saves and views iPhone text messages, photos and videos, phone call history, and other data, with export of conversations to PDF, HTML, or TXT.

Decipher TextMessage: Saves and views SMS and iPhone text messages, recovers deleted messages, and exports as TXT or CSV.

BackupTrans: Exports SMS and MMS messages to document files such as TXT, CSV, DOC, PDF, or HTML; available for Android and iPhone.

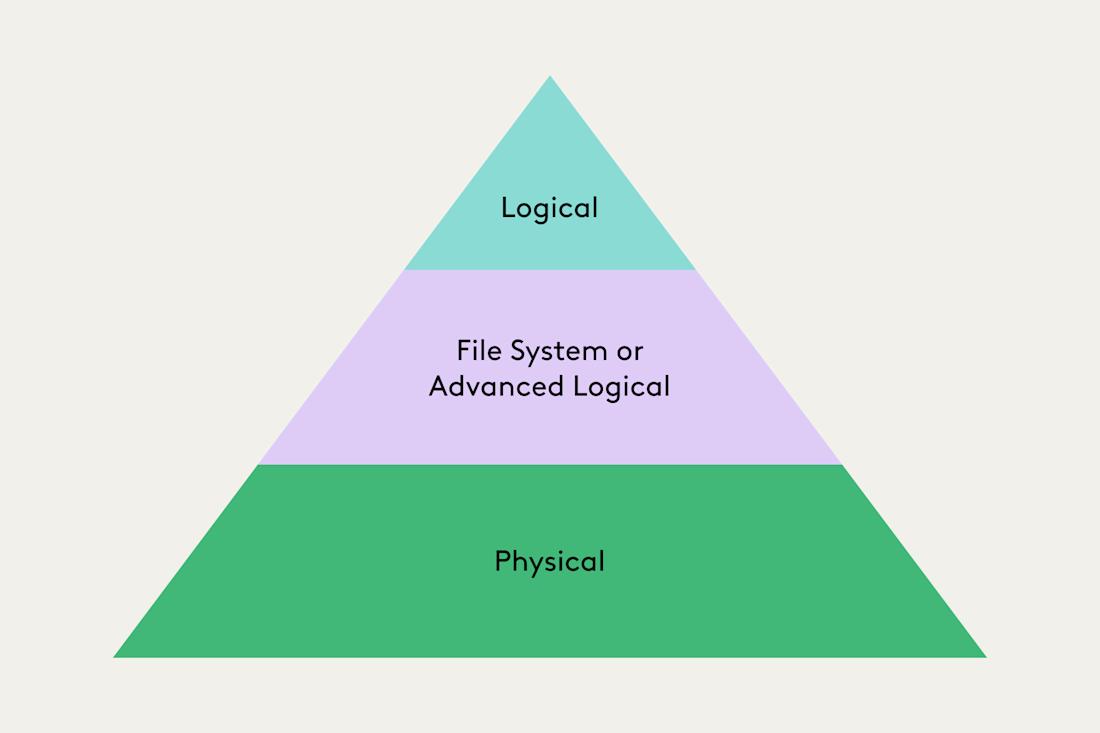

Forensic extraction is a comprehensive collection of a mobile device’s contents. This method is typically used with a Universal Forensic Extraction Device, or UFED, connected to the phone. There are three levels of forensic extraction:

Logical extraction: This is the quickest and most supported extraction method but also the most limited (live data export only), retrieving export call logs, SMS/MMS messages, images, videos, audio files, contacts, calendars, application data, and more.

Filesystem (or advanced logical) extraction: This method also accesses internal memory including database files, system files, and logs. Deleted data is available and recoverable via database files unless cleaned up via routine maintenance.

Physical extraction: This is a bit-by-bit copy of the entire contents of a mobile device, even including the flash memory. Full access to the internal memory of a mobile device is completely dependent upon the operating system and security measures employed by the manufacturer, and the device typically needs to be rooted (Android) or jailbroken (iOS).

Providers of forensic extraction tools include Cellebrite, MSAB, and Oxygen Forensics. Each provider offers multiple tools to support various forensic extraction needs.

When Are Personal Mobile Devices Discoverable?

Data on mobile devices is subject to discovery pursuant to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or FRCP, Rule 34(a)(1)(A), subject to privacy and confidentiality interests. The advisory committee notes to the 2006 amendment to FRCP 34 state the following:

“Inspection or testing of certain types of electronically stored information or of a responding party’s electronic information system may raise issues of confidentiality or privacy. …Courts should guard against undue intrusiveness resulting from inspecting or testing such systems.”

Discovery of data from mobile devices is also subject to the proportionality limitations set forth in Rule 26(b)(1).

The level of collection utilized depends on the needs of the case and the level of concern that evidence has been destroyed. For example, full physical extraction is often requested in IP theft cases to determine whether the defendant may have attempted to cover his or her tracks. However, courts typically require the requesting party to demonstrate a failure on the part of the producing party to comply with discovery obligations (including proof of evidence not produced) before authorizing a comprehensive forensic examination. “Mere skepticism” is not enough.

How Do You Process Imaged Devices?

One of the biggest challenges with non-forensic collection approaches is that the files typically aren’t in a format that is easy to review and produce. Text messages are individualized, so legal professionals must piece them together as conversations to evaluate those conversations in context.

Individualized file collections may be sufficient for certain messages, photos, or videos for collection and review. But it gets complicated quickly when reviewing on a larger scale – such as specific conversations, collections of photos, or the entire archive.

Conversely, UFED export archives may contain the entire archive, but the format is proprietary to the forensic extraction tool. UFED export archives are also tough to view and understand what the data means. It’s increasingly important to use an ediscovery solution that supports the ability to process UFED export archives and ingest the data in a manner that will facilitate review – including to display text chats in conversation format.

Key Case Law Rulings for Mobile Data in Ediscovery

Each year, important case law rulings come down involving mobile device discovery. Nine notable decisions are instructive for legal professionals tasked with discovery of mobile data.

Criminal Cases

Riley v. California (U.S. June 25, 2014)

The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in 2014 that police may not search the cell phones of criminal suspects upon arrest without a warrant. The opinion held that smartphones and other electronic devices were not in the same category as wallets, briefcases, and vehicles which are subject to limited initial examination. In his opinion, Chief Justice Roberts said that cell phones are “now such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that the proverbial visitor from Mars might conclude they were an important feature of human anatomy.” He added: “Our answer to the question of what police must do before searching a cell phone seized incident to an arrest is accordingly simple – get a warrant.”

Carpenter v. U.S. (U.S. June 22, 2018)

The U.S. Supreme Court held, in a 5–4 decision authored by Chief Justice Roberts, that the government violates the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution by gaining access to historical records holding the physical locations of cell phones without a search warrant. Before Carpenter, government entities could access cell phone location records by claiming the information was needed for an investigation. Following Carpenter, government entities must obtain a warrant in order to access the information. The ruling was very narrow and did not otherwise change the third-party doctrine related to other business records that might incidentally reveal location information. It also did not overrule prior decisions concerning conventional surveillance techniques and tools such as security cameras.

U.S. v. Sam (W.D. Wash. May 18, 2020)

In February 2020, the FBI removed the defendant’s phone from inventory, powered the phone on, and took a photograph of the lock screen, which showed the name “STREEZY” right underneath the time and date. The defendant filed his motion to suppress any evidence obtained from the examination of the phone. The court found that the FBI “physically intruded on Mr. Sam’s personal effect” and therefore “searched the phone within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment,” making the search unconstitutional.

Civil Cases

Calderon v. Corporacion Puertorriqueña de Salud (D.P.R. January 16, 2014)

In this case, the plaintiff produced relevant messages to the defendants but also admitted that some of the messages had been deleted from his phone. The defendants received ESI from the plaintiff’s phone service provider, which contained the plaintiff’s phone and text messages, including 38 that had not been produced. The court sanctioned the plaintiff by issuing an adverse inference instruction to the jury.

Lawrence v. City of New York, et al. (S.D.N.Y. July 27, 2018)

In a case involving claims against the NYPD after an alleged warrantless search of the plaintiff’s home, the plaintiff provided photographs that she claimed depicted the condition of her apartment several days after the incident at issue in the case. After a dispute over the photos, the plaintiff’s counsel agreed to produce the photographs’ native files (including metadata) which showed that 67 of the 70 photographs had been taken in September 2016, two years after the incident and immediately before the plaintiff provided them to her counsel. The case was dismissed.

Measured Wealth Private Client Grp. v. Foster, et al. (S.D. Fla. March 31, 2021)

In this case involving misappropriation of trade secrets claims, the court, having previously ordered a mobile phone forensic examination for a different individual defendant, granted the plaintiff’s motion to compel forensic examination of this individual defendant’s mobile phone, rejecting the defendant’s argument that the lengthy time period requested was a “mere fishing expedition.”

Sandoz, Inc. v. United Therapeutics Corp. (D.N.J. June 16, 2021)

In this case, the defendant asserted that one plaintiff had produced text messages that only hit on specific search terms and sought an order compelling that plaintiff to produce contextual text messages after the defendant and another plaintiff had already done so in accordance with the special master’s March 29, 2021, order. The special master granted the relief requested and ordered the plaintiff to produce additional contextual text messages.

Rossbach v. Montefiore Med. Ctr. (S.D.N.Y. August 5, 2021)

In this employment discrimination case involving claims of sexual harassment and wrongful termination, the plaintiff produced a text exchange that was determined to be a fabrication – in part because the version of the “heart eyes” emoji that was displayed in the text exchange was not supported by her iPhone 5 running iOS version 10. The case was dismissed.

In re Pork Antitrust Litig. (D. Minn. March 31, 2022)

In this class action for antitrust price-fixing for the price of pork, the court granted in part and denied in part the plaintiff’s motion to compel the defendant and the defendant custodians (who had been separately subpoenaed) to produce responsive text message content. In finding that the defendant did not have control over its employees’ text messages, the court denied the motion, but granted it with respect to ordering defendant custodians to find and produce text messages.

Download the court rulings from this chapter in PDF.

Best Practices for Reviewing and Producing Mobile Data in Ediscovery

When it comes to reviewing and producing mobile data in ediscovery, there are some best practices to keep in mind to support your case.

Reviewing Mobile Data

Reviewing begins with uploading the data in a format that facilitates review. To ensure the most efficient review of text and other nontraditional data forms, it is important to become informed about available tools and the file format(s) supported for ingestion and how they will display the data.

For example, when reviewing mobile device messages, Excel spreadsheets may be suitable for small volumes. However, large data sets require an approach that supports review in a manner similar to how the data would be reviewed on the mobile device itself.

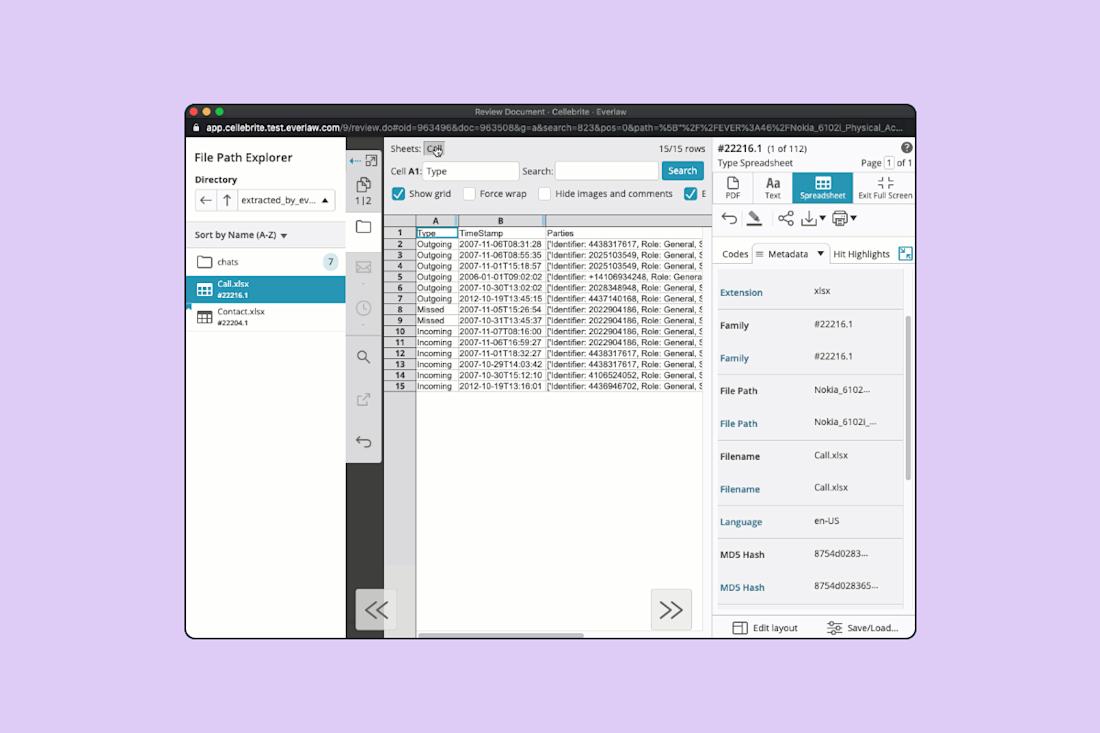

One example is Cellebrite, a digital intelligence company that enables law enforcement, government, and other organizations to extract data from cell phones. Its software can facilitate import into an ediscovery solution that supports several file formats:

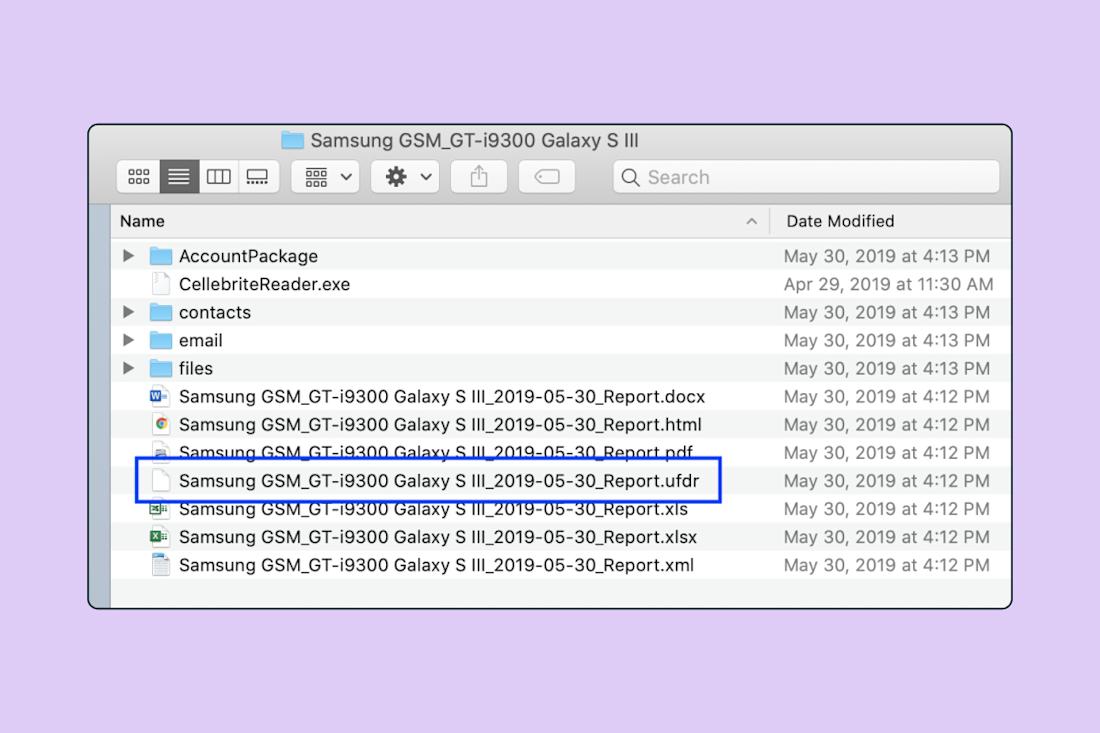

UFDR file format: A UFED export archive of the Cellebrite report can be the simplest way to upload data extracted from the mobile device.

ZIP file format: Uploading a zipped file of the entire Cellebrite export folder, including the report in XML format, can also ensure chat extraction, spreadsheets of other Cellebrite output, and file metadata.

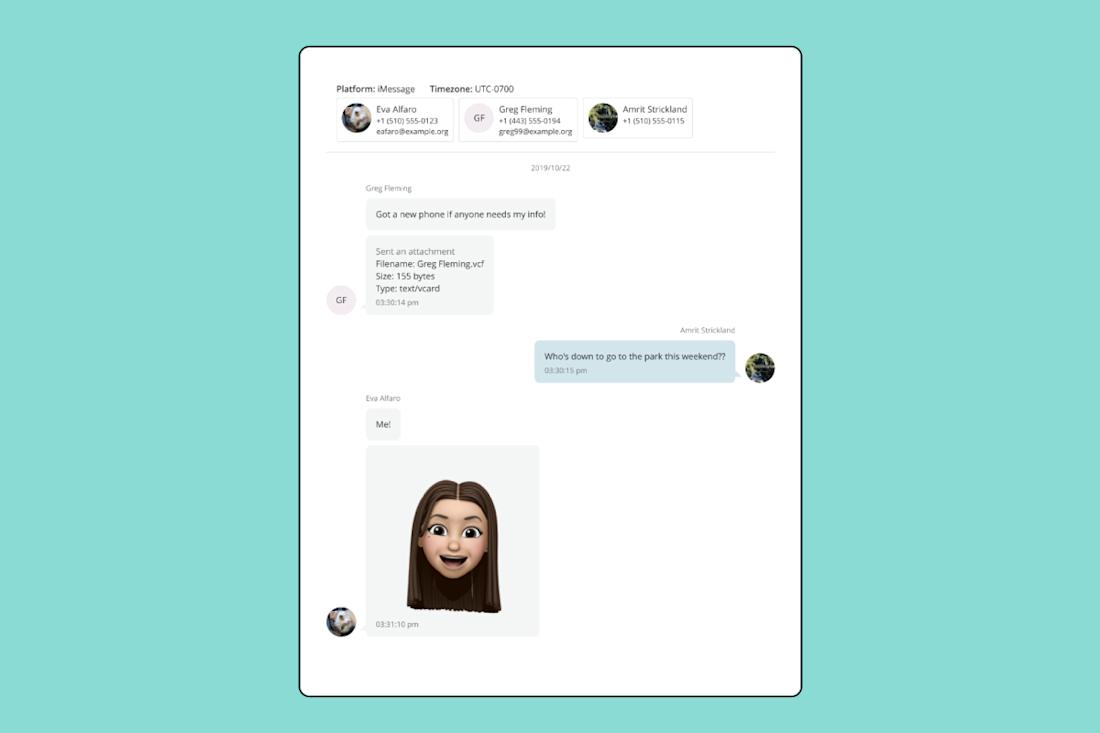

To effectively search and review chat and text messages, it’s important for short message data (SMS, MMS, and chats) to be rendered in an intelligible manner, similar to how they are viewed on the mobile device. This includes rendering conversations with chat bubbles, with app-specific visual formatting currently supported for iMessages and WhatsApp data. It’s also important for conversations to be kept together as distinct documents so that contextual messages can be retrieved as part of searches. The ability to import conversations into a reviewable format (such as PDF) will support the ability to review conversations in context.

Some conversations can span thousands of messages over a period of months or even years, so it’s also important to be able to split those conversations into smaller, more granular segments as needed to review them effectively.

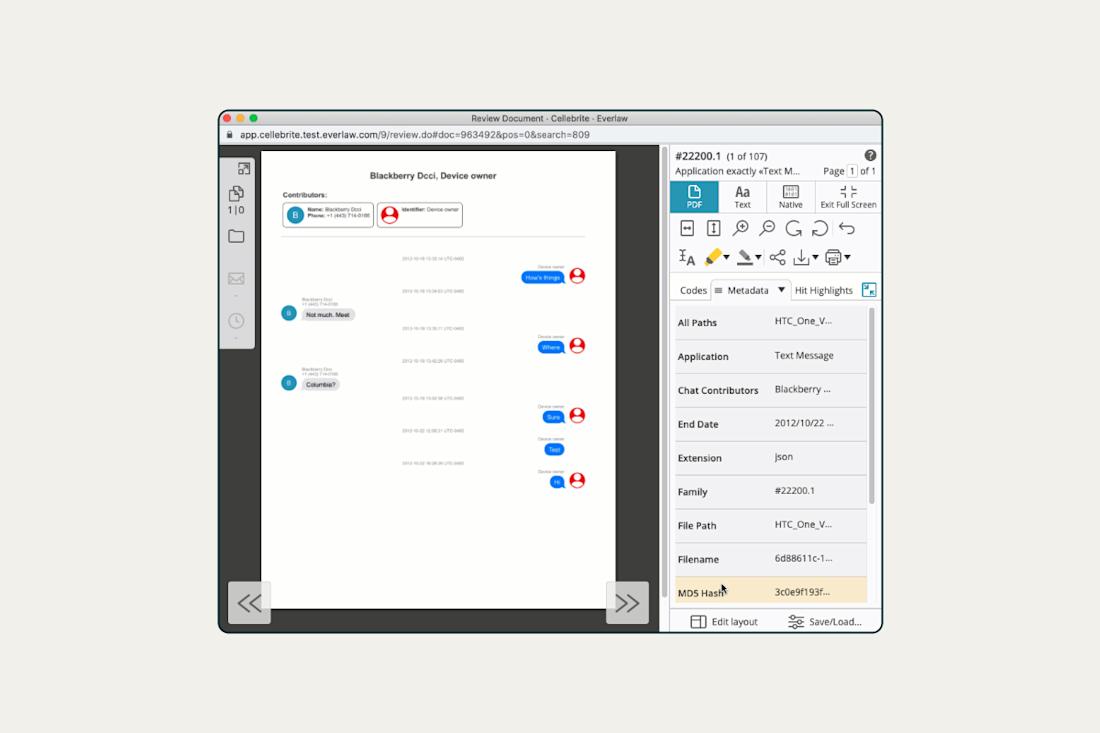

Everlaw users can review individual conversations in a document that displays the conversation name and its participants on its header, with images of the chat showing in-line. Non-images are extracted as children to the parent chat document. Everlaw automatically splits PDFs per 1,000 messages, with a special tool available to split PDFs into even smaller segments.

As is the case with any other type of document, it’s also important to be able to effectively view and search the metadata to filter based on criteria such as date range, chat contributors, etc.

The ability to review text and chat messages at the conversation level – and to be able to view and search the metadata associated with those conversations – is key to effective production of relevant messages in ediscovery.

The ability to support other types of data within mobile devices – such as contacts, call logs, and visited pages – is also important and the review methodology should provide an ability to see those lists in a spreadsheet format.

Producing Mobile Data

Absent agreement of the parties or a court order, a responding party must produce the information as it is ordinarily maintained or in a form that is reasonably usable.

Because of the unique characteristics of mobile devices and mobile device data, it’s a good idea to meet and confer at the outset of a case with opposing counsel regarding the necessary details for a successful document production.

Additionally, while hundreds or even thousands of text messages can appear in any given chain, it’s important to establish an understanding that only portions may be legally requested or obtained during discovery.

Finally, mobile device data requires customized quality control checks to validate the production. To avoid inadvertently producing privileged information or unintended data as part of your production process, ensure all fields being produced are determined and agreed upon beforehand. Be sure to also determine that direct links between data sets are not included when delivering native content. You cannot “unring a bell” when it comes to inadvertent productions.